Welcome to my site.

Curriculum Development for Contemporary Leadership Education

Dear Colleagues,

On Friday, March 13, from noon till 3 p.m., Dr. Peter Chiaramonte will return to campus to offer Marygrove faculty the second part of the workshop on leadership education he began last October.

The new workshop, “Curriculum Development for Contemporary Leadership Education,” will be an interactive session on using emergent complexity theory to develop a leadership curriculum that supports social innovation, individual creativity, and understanding the Marygrove identity.

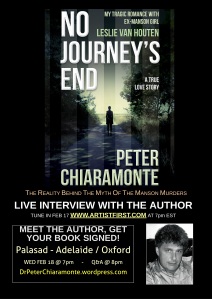

A native of Toronto, Dr. Chiaramonte began his career as a philosopher of leadership theory and practice with a BA and BEd from the University of Toronto, and an MA and PhD from the University of California. He has taught and lectured all over the world, including full-time professorial stints at the University of Western Ontario, UNC Chapel Hill, Dalhousie, Kennesaw State, Mansfield University of Pennsylvania, and Chapman University San Diego. He has successfully launched two master’s degree programs in Contemporary Leadership, and is working on his third. He is widely published on leadership education, and has also recently published his first nonfiction novel, No Journey’s End.

We are fortunate to welcome Dr. Chiaramonte back for this session to share theoretical and practical information on leadership, leadership education, and leadership curricula, drawing deeply upon his own extensive experience as a leadership educator and curriculum and program developer.

Seating is limited and advance registration is required. Lunch will be provided. You need not have attended Dr. Chiaramonte’s October to find this one valuable.

To reserve your spot, please email or call me (x1205) no later than Monday, March 9th. The location will be announced in the near future.

I look forward to seeing you at this timely and important event.

Don

Donald E. Levin, Ph.D.

Dean of the Faculty

Professor of English

Marygrove College

8425 W. McNichols Road

Detroit, MI 48221

www.marygrove.edu

What Led Me to Writing No Journey’s End: My Tragic Romance with ex-Manson Girl, Leslie Van Houten

What Led Me to Writing No Journey’s End: My Tragic

Romance with ex-Manson Girl, Leslie Van Houten

Peter Chiaramonte, PhD.

On August 5th 1977, after 25 days of deliberations in the Leslie Van Houten retrial for the first-degree murder of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca in 1969 Los Angeles—committed the night after the killing of Sharon Tate Polanski and four others—the jury reported to Judge Hinz that they were “hopelessly deadlocked.”

One of the jurors, Alphonzo Miller, told reporters that he changed his vote to “manslaughter” on the final ballot, split 7 (murder) to 5 (manslaughter).

“It was impossible for us to unanimously decide on whether she [Leslie] actually was responsible for her actions, and I doubt if you will ever find a jury that could.” I was there in court when the judge declared a mistrial.

That was over 37 years ago. Leslie Van Houten had already served almost eight years for her crime. By the time of her twenty-first parole hearing in 2018, Leslie—who was the youngest woman in the history of California to be sentenced to the gas chamber—will be about to turn 69.

She will have served all but the six months she was temporarily free on bond in 1978 in prison. Longer than Nazi war criminal (and close Hitler confidant) Rudolf Hess. (In 1987, Hess took an extension cord from one of the lamps in the Spandau Prison reading room, strung it over a window latch, and hanged himself at the age of 93.)

I knew Leslie since the time her original conviction was overturned in 1976, throughout her second and third trials for murder, and in the aftermath of the only freedom she was granted since first arrested and charged when she was just 20.

Having Mixed Emotions Writing About Somebody as Infamous as Leslie Van Houten

Looking back now after decades—as a professor who has been kicked in and out of some of what are arguably the best and worst universities coast-to-coast in Canada, the U.S., Europe, and as far east as Bangkok, Thailand—right from the start, I had this eerie sense that the space I had entered into by writing this memoir had more than a single dimension.

In order to tell a coherent, credible, and compelling story, I couldn’t pull any punches, or let the murders get in the way of my story. Nor do I try to revive Van Houten’s image or minimize her role in these crimes. (I get hate mail from both Tate/LaBianca bloggers and “high energy” attack dog lawyers on both sides.)

Striking a Deal With the Devil

Stroking his beard like Mephistopheles tutoring Herr Doktor Professor Faust, a colleague of mine recently remarked that “Books are much more than things to the author, they are a piece of your being, your soul.”

I’d been complaining about having to hawk my book now that it’s written, when all I really want to do is get back to writing the novel I’d already started—when the spark that led me to write No Journey’s End caught fire and took over.

Having surrendered my third green card to armed Homeland Security officers at the U.S. border in 2012 just happened to coincide with my daughter Mia discovering hundreds of pages of letters from Leslie to me. As well as some from Manson to Leslie. And with me suddenly having time on my hands to see how his mind works, I put my first novel and academic career work aside, and the months turned into years.

Déjà Vu

Reflections on criminal justice issues put in brackets for the moment— I’d like to go on record by saying that Leslie knew nothing about my writing this story until it was finished. I sent her a copy of the manuscript last September. I have no hidden or metaphorical axes to grind. All I wanted to do was write the best damned creative nonfiction, romantic adventure I could engender.

Mine is a true love story based on real people and actual events. The names of some secondary characters have been changed, some of who are, in fact, composites.

Then other in-synch events also conspired against and seduced me. Among them: Bennett Miller’s film Capote, starring Philip Seymour Hoffman in the title role, which I didn’t see until years afterwards. I immediately identified with Truman Capote’s compelling fascination with “something happening beyond and about me,” he said, “and I can do nothing about it.”

That impulse led him to write his classic nonfiction novel, In Cold Blood: A True Account of Multiple Murder and Its Consequences.

That poignantly pricked my emotions and, in due course, led me to this juncture. I felt the same way myself when I turned to page A-13 of the Toronto Star on December 28th 1976. Printed above the caption headed: “EX-MANSON GIRL RETURNS TO COURT WITH NEW IMAGE” were “then and now” photographs of Leslie Van Houten. I found the picture of the now Leslie alluring.

I had the distinct, hedonic sense that I was about to seduce somebody famous.

Who could resist writing about what happened next, and forever since?

On Creating Fiction & Nonfiction from Personal Experience

The Genesis of Any Story

More later, of course, but for now let’s suffice it to say that the genesis of any story is when you feel that unmistakable sharp, poignant prick of the emotions that resonates with the reality of your conscious experience. This often heralds the beginning of a story. I liken this to finding bits of precious stones caught in a web or realm of meaning that surrounds you. First you sense a vibration, find a few diamonds in the rough, chase them down, and discover the mother load.

A writer cannot know in advance what may, as Curry puts it in her book, “kindle the spark.” The spark that invariably causes the mind to begin its marvelous and fantastic journey of sorting through the rag and bone shop of experiences that may become a story. Or, as she says,

What the writer needs to approach his writing is that genesis or source, that kindling spark that sets his imagination afire. Without this he could spend a lifetime stacking up dead timber in terms of story material and never have anything to start the fire (page 21).

When I first began No Journey’s End I had several firm advantages in terms of raw data. For one thing, I have been a lifelong diarist and began detailed daily entries in 1975, which I’ve kept for over forty years running. I haven’t missed many days. In fact, I’ve not missed more than 20 days out of the last 14,600. I have them here with me now in this room. In future FURTHER NOTES I will scan a few as examples of what I will be talking about in terms of how to keep simple, yet worthwhile details in daily records. A truly invaluable tool for any writer. But, as I say, I also had hundreds of pages of letters, pictures, and notes from Leslie to work with; a library of great books; and Internet access to data bases, including the Los Angeles Times and Toronto Star newspapers. There was more.

But when would lightning strike the wood pile and ignite the dazing-coloured lights of my imagination? Then something else happened. I felt another sharp tug on the wire…

Déjà vu

Director Bennett Miller’s film Capote, starring Philip Seymour Hoffman in the title role, came out in 2005, but I didn’t see it until several years later. However, when I did see the film it caused me to reread a Christmas present my ex-in-laws gave me in ’88, Gerald Clarke’s biography Capote (1988).

Truman Capote and another favorite author of mine, Norman Mailer, appeared on David Susskind’s program Open End in 1959 to talk about writers and writing. Mailer defended the Beats, such as Jack Kerouac, when Capote attacked them. “None of them can write,” he said, not even Mr Kerouac…[It] isn’t writing at all—it’s typing.” Ouch. Okay, so Truman wasn’t right about everything, but when I turned the page to 317 in Clarke’s book something else bit me. Hard. Here’s what I read:

[Truman’s] mind was really on nonfiction. “I like the feeling that something is happening beyond and about me and I can do nothing about it.”

In that mood he opened The New York Times on Monday, November 16, 1959. There, all but hidden in the middle of page 39, was a one-column story headlined, “WEALTHY FARMER, 3 of FAMILY SLAIN.” The dateline was Holcomb, Kansas, November 15…

That pricked my emotions. Those of you reading No Journey’s End will recognize the similarity to the spark that sets my story off at the end of chapter one, “A Certain World.” Reading the Times led Capote to write In Cold Blood. Now some parallel, inciting incident was about to set off my nonfiction novel as well:

I wasn’t writing to the girl with the ‘X’ on her forehead. I was writing to the beautiful young woman with the dark hair, pouty lips, and wide-eyed good looks. When I read about Leslie getting her second chance to be free of that madness, I felt duty-bound to let her in on my own journey for freedom and independence. I felt sure she’d have one hell of a story to tell if I met her. Try as I might, I could not fall asleep right away. This was my second restless night in a row. I cut out the newspaper photo of Leslie and propped it up on my desk where I could readily see it. When I woke up in the morning, the first thing I did was to re-read the “Ex-Manson Girl Returns to Court with New Image” Toronto Star clipping, and then reviewed those “then and now” photos and dog-eared pages from Helter Skelter.

I had the distinct, hedonic sense that I was about to seduce somebody famous.

The Writer’s Blood

You see the parallels, with a twist. That’s the point at which my story takes off from. My theory is this: The proposed sense of recognition in any creative writing involves achieving a good match between the present experience and our “rag and bone shop” of language, history, and past experience. The reconstruction we do in creative nonfiction may differ from the original events that we “know” we have experienced before in some form—and even though they must be condensed and refined into a coherent tale, they are still nonetheless “true.” Or in the case of pure fiction, not as true perhaps. Or perhaps, even more so. But it’s all based on some fundamental, conscious experience that belongs only to you, the writer. Only makes sense. Now it’s your job to share what you know to be true with others who feel the same way about what they write and do.

What makes a story isn’t the material you might reach out and collect off the shelves or out of boxes, like packaged fruit. As Curry reminds us, “What makes the story is the tree the writer allows to grow from deep in himself [or herself], sprouting from that first small seed of impelling interest. It is the tree watered by the writer’s blood, fed in the soil of his memory, and towering toward heaven in the sun of his imagination” (page 30).

Now back to work for you and me too. See you again soon I hope with “Further Notes 3, Writing in the Climate of Identity and Realms of Emotion.”

A Review of Slaughter and Rhoades’ Academic Capitalism and the New Economy, Chapter 12:1 “The Academic Capitalist Knowledge/Learning Regime”

A Review of Slaughter and Rhoades’ Academic Capitalism and the New Economy, Chapter 12:1 “The Academic Capitalist Knowledge/Learning Regime”

Peter Chiaramonte

You can see why I may have been hesitant to include the title of American professors Sheila Slaughter and Gary Rhoades’ final chapter in the heading for this review. “The Academic Capitalist Knowledge/Learning Regime” is more than a mouthful. What’s more, the authors repeat the phrase so often it becomes a mantra that can make you woozy. Don’t get me wrong. It’s a wonderful conclusion to a brilliant book but, if you had to try teaching it to someone else, language such as “propertized” “interstital” and “intermediating organizations” might trip you up in the seminar hall. Is it worth getting tongue-tied just the same? You bet. Here’s why: “The reason a writer writes a book is to forget a book and the reason a reader reads one is to remember it.” I’m no Tom Wolfe but I would like to tell you something about a book worth remembering in spite of its flaws.

Students and scholars of higher educational systems will find many references to this rather seminal work cited in academic books, magazines, and journals. All tongue- tying neologisms aside, professors Slaughter and Rhoades provide a very thorough and impressive treatment of the key issues as they see them. First is their theory that, in the new economy, knowledge is becoming viewed more and more as just another raw material intended to serve corporate interests in developing, advertising, and selling educational and research products in the private marketplace. The authors cover a wide range of topics to verify each of these points—including the multiple expansion of managerial capacity, intellectual property patenting, copyrighting, networking, marketing, and so on. Elsewhere in the book they occasionally touch on the replacement of full-time tenured faculty with part-time contingent faculty—primarily as a cost savings priority.

Here in the final chapter, once again the authors get into the extensive growth of non-academic middle managers hired to handle the infrastructure, economic development and entrepreneurial activities of the academy. But they do not explicitly connect this to the whirling paradoxes of having non-academic managers so embedded in university business. This in spite of the fact that even when “institutional expenditures go up, expenditures for instruction go down” (p. 332). What Slaughter and Rhoades in my mind fail to address—despite solid grounding in Foucault’s “disciplinary regimes,” 1980, and Castell’s notion of “the network society,” 1996—are the so-called “bureaucratic effects” embedded in this system. Although they must clearly recognize how bureaucracy itself can become a disease for which it purports to be the cure, they overlook some of the “systemantic” (John Gall, 1975) ways in which academic and capitalist bureaucracies not only solve problems but create them as well.

To their esteemed credit, Slaughter and Rhoades do strike more than a glancing blow at the incongruities inherent in academic institutions moving to intersect more with corporate interests than social ones. The fundamental idea of the college or university as a public domain and forum for discussion, debate and critique is, as they say, “pulled to the background” (p. 333). Instead of high-caliber teaching and research, the authors suggest that universities may increasingly come to represent factories for the manufacture of employees for the new economy.2 Therefore, by and large for me the foremost implication of the book is that higher education systems have become systems for the manufacture, distribution, and consumption of knowledge as a commodity. This shift, according to Slaughter and Rhoades, has taken us from a “public good” paradigm to one of “academic capitalism.” They conclude that this swing toward values of privatization and profit making in our society has given individual corporate and institutional claims on new knowledge priority rights over the public good. The subplot is that higher education is ever more at risk of becoming a mere instrument of economic policy and of very little else.

Slaughter and Rhoades do a terrific job of highlighting the many fault lines that blur the boundaries between public and private sectors yet nonetheless sustain a substantial level of public subsidy of higher education (p. 329). Furthermore, in their view, academic capitalists are apparently not very successful at generating net revenues. Although colleges and universities present their commercial activity as being of benefit to all—the economy, educational capacity, and so on—there is evidence that academic institutions are not as it turns out very good capitalists. For example, Slaughter and Rhoades report that while technology transfer brings revenue in, it also takes much of it away in legal fees and costs for the maintenance of technology transfer offices. The differences between debits and credits even I can figure out.

As unmistakably concerned as the authors are about these issues, they are also pragmatic in recognizing where lies the true crux of the matter. They see a change from what, at the time of Sheila Slaughter and Larry Leslie’s previous book—Academic Capitalism: Policies, Politics and the Entrepreneurial University (1997)—they had already begun to understand: that the pursuit of market activities to generate external revenues has distorted the boundaries between markets, states, and higher education. Here in the more recent book (2004) Slaughter and Rhoades still do not see the new regime as having necessarily overthrown the previous one, but they have recognized how unnerving this overlap of the two domains has become.

In any case, this overlap (or collusion if that’s not too strong a word for it) between early twenty-first century academic and economic regimes is unlikely to go away any time soon. I only wish the authors of Academic Capitalism and the New Economy had written about all of this in the language of their shorter piece for American Academic (Rhoades and Slaughter (2004) “Academic Capitalism in the New Economy: Challenges and Choices.” Vol. 1, Issue 1, pp. 37-59). This is, in my opinion, an appreciably more readable version of their call to “republicize” colleges and universities. In a superb review of Academic Capitalism and the New Economy in the Education Review by Rebecca Barber (www.edrev.info/reviews/rev453.htm) she also felt that, although Slaughter and Rhoades give us very finely distinguished coverage of the issues, the style and vocabulary of the book can be confusing and off-putting much of the time. I certainly agree with that. The manuscript needs another good line edit. Less Tom Wolfe next time and more Ernest Hemingway. I submit they consider renaming this chapter “The Capitalist Knowledge Regime.” It’s less redundant and more or less stands for the same disturbing phenomena. Besides, it’s an easier title to remember and repeat.

The Book Leslie and Her Lawyers Don’t Want You to Read

The book Leslie Van Houten and her lawyers don’t want you to read. Why is everyone always angry about the truth, although they claim to believe in it?

The only thing, I believe, Leslie Van Houten and her lawyer could possibly object to in my story are (perhaps, I’m only guessing) some of the details regarding her life before and after I knew her. In which case, I’ve already made this perfectly clear: I tell my story in a coherent way so the reader gets to know her as I did, from media reports initially, then through our letters, then in person, together, and finally how it all tragically came apart in the end.

If there’s an error in the books I was reading, or in the newspaper reports I encountered as my plot unfolded—then the mistake lies with them, not me. My story is perfectly accurate in the manner in which it is told. I make it clear these were the exact sources we were all given at the time.

As for the rest, what Leslie and I wrote about and spoke about is all well documented and confirmed by diaries, tapes and personal letters.

Further Notes on Writing a Nonfiction Novel

Further Notes on Writing a Nonfiction Novel: No Journey’s End: My Tragic Romance with ex-Manson Girl, Leslie Van Houten. A True Love Story.

by Peter Chiaramonte

People are always angry about the truth, although they claim to believe in it. ––– Charles Bukowski

Dr. Algis Mickunas, one of my great old professors when I was starting out at Ohio U at the end of the sixties used to say; “Writing is harder and more impenetrable for writers than it is for other people.” I still believe this is true. It takes a lot of courage for one thing, to become a writer. And this process begins long before you’ve written a page.

There’s this wonderful little book by Peggy Simson Curry, (an adept and respected writer from the American West), who I’d like to recommend to you in the context of creative nonfiction writing. Curry drew upon firsthand experiences during the halcyon days of ranching life and also worked in the oil fields during the 1950s and 60s. The book is called Creating Fiction From Experience (1964), and I recommend it to anyone serious about writing a memoir. All stories are fiction to the extent that in order to tell a coherent, credible, and compelling story—the author must generate, select, and edit from an overabundance of facts in order to enlighten and entertain. Curry’s guidebook provides several wonderful advices for getting started and remaining on course to the end.

To begin a realistic story, you must first put aside any temporary fear of the impossible and—against all odds—begin the attempt with faith and courage in the work itself as its own reward and justification. All writing is practice writing after all.

Peggy Curry said, “Never allow yourself to be afraid no one will consider what you write worth writing.” Only you can decide what to say or not say according to what inspires you to deliberately explore your own feelings and thoughts (page 6- 7). And no one can know the worth of your story until after it is written. Don’t let the pezzonovante tell you any different. Confident in having been in no way negligent right from the beginning, be prepared to stand your ground.

What, asks Curry, is this truth the creative person must know? Her answer is: “It is all vital experience that strikes us so sharply that a part of us says, ‘this is real. It is here.’ It is when the surge of the blood, the clarity of the mind, the twist of the heart tells us life is happening” (page 13). And, if we are “creative nonfiction” writers, I should add her point about still having the obligation to gain control of what we know by way of artistic patterns.

For example, in the case of No Journey’s End I felt compelled not to put any words into my characters mouths that couldn’t be vouched for. So I needed to find creative ways to accomplish this stringent requirement. For instance, in writing about personal exchanges between Leslie Van Houten and myself—I’d start with my diaries and daily newspaper accounts, and overlap these with Leslie’s letters. Since I couldn’t make the entire book about the letters alone, I began matching the dates of our face-to-face conversations with things we were talking about at the same time in our letters. That way I didn’t stray from the language and topics we were discussing in real time, nor did I invent topics we hadn’t actually discussed. Plus, I took photographs and let Leslie know I was tape recording our phone calls. The Los Angeles County Jail and California Institution for Women inspected our mail and monitored our conversations as well.

The palest ink is stronger than the greatest memory

Where does the urge to record the impact from source impressions, reflection, or recognition from personal experience come from—if not from the actual experience itself? Writing dialogue, I found, reduces the number of words needed to convey the same thoughts. After 10,000 hours or more of writing creative nonfiction, one gets to know intuitively what words are right without knowing why. Scenes and paragraphs appear out of the ether as we scratch away draft after draft— paradoxically moving further away from our precise rough notes to an even closer refinement of the meaning of symbols we’ve written down. I liken the whole process to sculpture.

Something magical happens when you discover that you possess knowledge you didn’t know you had. It just feels right, honest, and alive. Curry calls this “a discovery of the most memorable truth.” You’ll know it when you feel it so be sure to chisel it down with the sharp end of your pencil.

“What do I know of truth?” she asks.

Ask yourself as a writer: “What has happened to me and touched me so firmly and finally that I will live with it always? I know of no satisfaction greater than that of developing the ability to express oneself fully and accurately.” There lies the source of the ultimate truth we are after.

Further Tips on Beginning & Becoming a Paperback Writer

Peggy Simson Curry reminds us: “We must always remember that to breathe the essence of life into people on paper is a subtle and elusive act of skill and imagination, of knowledge and reaching beyond knowledge, of the conscious and the subconscious made articulate.”

Begin to explore, through memory, what you have felt, what you can’t forget…Be free…You are simply expressing what is yours (page 8).

And in the end: Curry admits that perhaps she’s old-fashioned, but glad she went to school when teachers read what she wrote and took an interest in her as person. “The writer,” she says, “must express himself because he is an individual in a world where individuality is fast disappearing.” She wrote that in 1964—more than half a century ago. I had just turned a teen and grew up in that brave new world not, she was writing about.

We live in a universe where each of us must search for the meaning of himself. A world “in which man must never be so confused or so harassed that he cannot think his own thoughts and develop them into expression … is the world in which no one should be ashamed of emotion, but glad that he is capable of feeling it.” A writer’s obligation to himself and to others, Curry concludes, is to put down firmly and honestly—and beautifully—what he or she knows to be true.

Manson’s Real Motives for Murder & the Context for Malice Aforethought

Manson’s Real Motives for Murder & the Context for Malice Aforethought

Peter Chiaramonte

The first time I read Helter Skelter in 1976—where my novel begins—I found the writing, if not the logic or characterization—majestic. More recently, reading Jeff Guinn’s Manson I felt just the opposite: the logic was sound but the writing as mundane as Curt Gentry’s was polished. For insight, I found Roman, by Polanski, most enlightening and entertaining. But the mainstream source that I found both suggestive and revealing about our times and culture overall, was Jonathan Gould’s wonderful book about The Beatles, Britain, and America, Can’t Buy Me Love.

By putting this entire catastrophe within confirmable frameworks I hoped to better comprehend—among other unsolved mysteries about this case—why music producer Terry Melcher, and Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson, didn’t go to the police right away—before the LaBiancas were assaulted—and explain to detectives and the District Attorney why they should be questioning Charlie Manson about what happened at 10050 Cielo Drive?

So You Want to Be a Rock ’n Roll Star…?

Where’s the distinction in that?

When his (delusional) preordained rock stardom in 1969 just wasn’t happening, Charlie became ever-more paranoid and violent. He could feel the heat closing in. He knew he would need lots of money to pack up his Family and hide out in Death Valley. That is, he imagined, before the Black Panthers invaded Spahn Ranch and attacked him. Because those were the kinds of delusions this bozo was under. Because Charlie Manson was a racist, his hallucinations tended to take that form. That’s what you see when you’re on acid. The distinction between what’s going on inside you and what you see on the outside become blended, blurred and disturbed. In Charlie’s case—metaphorically speaking—this was a short ride on an awfully swift bus.

Excerpt from No Journey’s End, chapter 7, PLEASE TELL ME YOU’VE MISSED ME:

***

Both Leslie’s boyfriend, Bobby Beausoleil, and Charlie Manson imagined themselves making inroads into the recording industry. The whole reason Manson decided to move his Family to LA in the first place was to make a name for himself in rock music. Both he and Bobby felt they had all the talent they needed in hand. What they lacked were contacts directly inside the business.

Then, along comes Dennis Wilson of the rock band The Beach Boys, driving his silver GT 250 Ferrari. Wilson stopped one day to pick up Patricia Krenwinkel and another Manson girl called ‘Yeller,’ who had their thumbs out. The girls went with Dennis back to his place for a full-on sexual frolic like the three- some in A Clockwork Orange—the scene Stanley Kubrick set to the rhythm of the “William Tell Overture” in fast forward.

The Manson girls didn’t really know who Wilson was, but, when they told Charlie about the event, he knew right away what that meant. He insisted the girls take him and the rest of the Family back to Wilson’s house at 14400 Sunset Boulevard—a beautiful log cabin estate first owned by Will Rogers. It was similar, in fact, to the one Wilson’s friend, Terry Melcher, rented with his girlfriend actress Candice Bergen way up in the clouds above Benedict Canyon.

When Dennis pulled into the driveway, he could already hear loud Beatles music playing and noticed a party going on with his house full of girls running ’round naked. When he opened the door, there stood all five feet two-and-a-half inches of Charlie Manson. Manson dropped to his knees to pay homage to a rock and roll legend, first by kissing his feet, then by offering Dennis drugs and whatever, or whomever, however often he wanted. He was welcomed to have all the girls one at a time or in countless formations.

Since the girls reliably proved themselves willing to engage in whatever drug-induced sexual fantasies Dennis desired, The Beach Boys drummer consented to Charlie and these nubile groupies staying at his house, eating his food, driving his cars, and peeing in his pool, if they had to. Not known for his brains, style, or good sense, Dennis thought Charlie was some kind of deep thinker. But, more than that, he was seduced by the orgies Manson set up for him and his friends who fancied chasing sexy, naked sprites and fairies around the pool. Someone should have thought to invite Roman Polanski.

Before what there was left of Wilson’s milk of human kind- ness had completely run dry, Manson put the bite on every celebrity musician who showed up at Dennis’ door looking for a party. Besides Dennis’ famous brother, Beach Boys composer Brian Wilson, Manson was introduced to another bona fide rock legend at the house, Neil Young. One time when Young came by the house, he tried to improvise a few chords on the guitar to go with the insane lyrics that Charlie made up on the spot.

And, later on in the recording studio that Brian Wilson had in his house, Dennis had an engineer try to record some of Charlie’s singing and playing. One song Charlie thought would make him a star was sophomorically titled, “Ego is a Too Much Thing.” At least he was partially right about something. But, of course, nothing came of the demo.

Regardless, Manson kept on bugging everyone to help find him a record deal with some major label. He had started to piss some people off. People like Mo Ostin of Warner Brothers Records had heard the demo and said they weren’t interested. However, Terry Melcher, a musical producer at Columbia with more than eighty top-selling hits to his name (including those by The Byrds and Paul Revere and the Raiders), hired Dennis Wilson’s friend Gregg Jakobson to find him new talent. In ex- change for getting him stoned and laid on a whim, Jakobson promised Manson he would bring Terry Melcher to hear Charlie sing.

Dennis Wilson and Gregg Jakobson finally succeeded in dragging music producer Terry Melcher to Spahn Ranch to give Charlie Manson a listen—complete with a backup chorus of naked strippers that Charlie choreographed for himself.

Jakobson said he hoped to capture the “spell” Manson and Beausoleil had cast over their rapt cult of women. But, reading this, I got the impression Jakobson might just be trying to get himself laid.

Charlie felt sure a recording contract would be soon to follow once Melcher heard him play, and he told the girls what they must do to help make this happen. Although Melcher’s assessment was that the music did not merit further time or investment—not to appear rude or ungrateful—the producer shone Charlie on.

“You’re good,” he said, “but I wouldn’t know what to do with you.”

Of course, Melcher never returned any of Manson’s phone calls, hoping that he’d get the message. He got it all right, but it wouldn’t suffice. Not by a long shot.

As Melcher and Wilson were leaving Spahn Ranch, Manson invited himself along for the ride. He took his guitar and hopped into the jump seat of Wilson’s Ferrari. When they drove Melcher home, Charlie got out to see where the son of Doris Day lived with his girlfriend Candice Bergen. He wasn’t invited in.

He and Tex Watson returned to that same address (10050 Cielo Drive) more than a few times after that, ostensibly looking for Melcher, even after Terry had moved out and the Polanskis had taken the residence over. And since Melcher kept putting him off (in order to save face), Manson reframed this rejection as an insufferable treason. And you know what they do to traitors.

Terry Melcher returned once again to hear Charlie audition at Spahn Ranch. Not so much because he’d changed his mind about Manson’s singing, but because he was partial to having sex with a cutely attractive, precocious teen named Ruth Ann Moorehouse, aka ‘Quisch.’ Her name was derived from the sound most men made the first time they saw her: “Ooh whee!” Unlike Dennis Wilson—who would do just about anyone—and Gregg Jakobson who was happy to lick up the leftovers, Melcher promised to return to hear Manson audition in exchange for another romp. Somehow Candice Bergen caught on and put the nix in on that. She knew what was going on with Terry even if Charlie didn’t. And however groovy Charlie’s songs may have sounded to fanatics ripped on mesc and meth at the ranch, Manson’s songs made little impact on a veteran critic like Melcher. He went for the Quisch, not the magic.

When Melcher didn’t show up as planned, Manson went ballistic. His unwarranted sense of prerogative made him high dudgeon and fuming over this blatant rejection. He was frantic to find Terry and bring him back to the ranch so he might save face with his brethren. He drove to the house at 10050 Cielo Drive, but Melcher didn’t live there anymore. The landlord, business agent Rudi Altobelli (who was washing up in the guest house) asked Charlie to leave.

The next day, during a flight to Rome, Sharon Tate asked Altobelli, “Did that creepy-looking guy come back there to see you?”

She had been face-to-face with the Devil himself.

In order to save face and keep faith with his followers, Manson made up a tale about Melcher having deliberately betrayed him and the Family. Charlie made Terry into a villain of Biblical proportions, saying he’d promised a contract for lots of money then reneged for no reason. Surely treachery of such magnitude must be a sign of the oncoming Apocalypse? For sup- port, Manson referred his followers to what was proclaimed by The Beatles as well as the Bible. All the more reason, Manson told his disciples, for them to ready themselves and surrender to the divine magistrate of Helter Skelter. It was on.

Being on peyote and singing along around the campfire, Charlie’s visions and songs may have sounded like prophecy, but, deep down, Manson’s take on “Helter Skelter” was primarily an excuse for settling a score. And being a con man par excellence, he could make up a legend as he went along. He wanted to scare the bejesus out of everyone and get Beausoleil to clam up about who ordered the hit on Hinman and why. Besides sending Terry Melcher, Dennis Wilson and their stripe a pretty clear message, Charlie thought he could combine this myth with a plot to get Beausoleil out of jail or at least make Bobby think so. So he and the others would keep quiet about such goings on.

It angered Manson, who liked his followers to think of him as the ‘fifth Beatle’, when his message wasn’t embraced—let alone paid no attention at all. But who could blame Terry Melcher for passing on songs with such lines as “Cease to exist?” Pretty telling—though not exactly “Cortez the Killer.”

It didn’t matter how many drugs you had taken. Manson’s lyrics all sound like gibberish to me, and I’ve written a few bad poems in my time. Except that a very pretty girl I was eager to know better had at one time taken this runt and his wearisome banter to heart. So what did I know? Dennis Wilson thought he saw something in Charlie’s song about getting a girl to submit herself and let go her ego to the point that she ceased to exist. Working on his own, Wilson recast the lyrics. In his version, the singer is asking the girl to cease to resist—which was more to his liking. He changed the title to “Never Learn Not to Love,” and he and his brothers, The Beach Boys, recorded the song on their label. Thinking about the hundreds of thousands of dollars the Manson Family’s invasion had already cost him, Dennis listed himself as sole composer, cutting Charlie out.

When Wilson told Manson that he’d recorded his song with The Beach Boys, Charlie at first was elated. He expected “Cease to Exist” to appear on the next Beach Boys album that winter. But instead, The Beach Boys released “Never Learn Not to Love” as the B-side of their new single, “Bluebirds over the Mountain.” And, of course, there was no mention of Charles Manson.

To Charlie, this represented yet another timeless disloyalty in the long saga of persecution he’d claimed to have suffered for thousands of years. There was sure to be hellfire and fury whipped upon the backsides of those rich and famous that dared dick around with the Devil.

According to what Jakobson later wrote in Rolling Stone un- der a pseudonym, Charlie once gave Gregg a .44 caliber slug to pass along. “Tell Dennis I got one more for him,” said Manson.

In another credible report, Manson once held a knife to Wilson’s throat and asked, “How would you like if I killed you?”

Wilson tested, “Go ahead, do it.”

Fortunately for him, Charlie was more mouth than action. He’d always pissed far more than he’d drunk.

Wilson eventually cut his loses. Finally sick of all the theft, destruction and lies visited upon him by these worm-festered squatters, Dennis defaulted on his lease and left the Manson clan there on their own to await the sheriff’s eviction. All tallied— what with all the stolen items, dental treatments and serious damage to an uninsured Mercedes-Benz—Dennis Wilson was out hundreds of thousands of dollars. The medical bills alone had been staggering, especially after the girls all suffered an out- break of virulent gonorrhea.

After they were kicked out of the house on Sunset Boulevard, things back at the ranch with Charles Manson became even more crazy and violent. One sign of the changes taking place at the end of the summer of ’69 was how obsessively Manson kept playing The Beatles White Album over and over again with everyone tripping like mad whores on acid. He’d program these malleable teens with endless mantras and repetitions.

“Can you hear it? Can you hear it? Can you hear it? They’re speaking to me. They’re speaking to me. They’re speaking to me…”

Crap upon piles of crap like that ad infinitum. Can you imagine the effect that would have on your mind over time? Especially if you’d taken to dropping a hit or two of pure white Owsley acid?

Sometimes Manson needed more than drugs and hypnotic suggestion to keep the stronger-willed girls like Leslie and Patricia in line. That’s why he kept them away from outside influences that might challenge the dogmas he was spewing.

More and more of Manson’s canons had to be memorized. Junk like: society is corrupt; forget everything your parents and teachers taught you; there is no right or wrong, good or evil; life and death are the same thing; death is the next step on the way to creating a better life. What a mix: naked nymphs, programmed ego killing and moral abandonment. Something for the whole Family.

And Manson had other more conventional ways too of weaving his evil magic. Once, when Pat Krenwinkel managed to escape and get pretty far away, somehow he found her. (Just how far she got I’d be sure to ask Leslie.) That fact alone was enough to frighten her into believing there was no escaping his power. And one time when Leslie had been grumbling about being ordered to have sex with some of the bikers, Charlie threw her into his dune buggy and drove to the top of the Santa Susana Pass, where he dragged her to the edge of a steep cliff and told her, “If you want to leave me, go ahead jump.” Because that was her only alternative to staying. So Leslie ended up staying so long and doing so much and many drugs that it no longer mattered. She had little individual sense of self left and what there was had nowhere else to go at the time.

***

Throughout the last half of 1969, the ranch owner George Spahn had begun asking his men to run an increasingly violent, deluded and megalomaniacal Charles Manson and his Family off of his property. This was being encouraged in particular by one of his ranch hands, Donald ‘Shorty’ Shea. The big record deal Manson was counting on never ensued and the Family had al- ready been kicked out of Wilson’s cabin on Sunset Boulevard. Things weren’t looking so rosy for Charlie.

When his preordained stardom just wasn’t happening, Charlie became ever-more paranoid and violent. He could feel the heat closing in. He knew he would need lots of money to pack up his Family and hide out in Death Valley. That is, before the Black Panthers invaded Spahn Ranch and attacked him. Because those were the kinds of delusions this bozo was under. Because Charlie Manson was a racist, his hallucinations tended to take that form. That’s what you see when you’re on acid. The distinction between what’s going on inside you and what you see on the outside become blended, blurred and disturbed.

Members of the Straight Satans motorcycle gang were of course similarly racist outlaws whom Manson hoped would become his protectors. They were planning a wild and wicked orgy up at the ranch one summer weekend. So they sent Bobby Beausoleil to buy a thousand tabs of mescaline from his “friend” Gary Hinman. Hinman, who in addition to going to graduate school at UCLA, manufactured his own methamphetamine and mescaline in the lab in his basement. The bikers later claimed the drugs were tainted and demanded their money back. So Manson seized this opportunity to embezzle even more cash from Gary, who was rumored to have recently inherited tens of thousands of dollars. At least that’s what Mary Brunner had heard and passed on to Manson.

On July 25, 1969, just two weeks before the killings at 10050 Cielo Drive and 3301 Waverly Drive, Charles Manson sent Bobby Beausoleil, Susan Atkins, and Mary Brunner (the mother of Manson’s child) to pay Hinman a visit at his house in Topanga Canyon. Since at one time they had acted as friends, at first there was no cause for alarm. Bobby had often used Gary’s place as a crash pad to hang out, fuck around and do drugs. But very soon the intruders, who came armed with a knife and a gun, began demanding their money back for the mescaline Hinman had sold them to pass on to the Satans.

When Hinman tried to grab the gun from Susan Atkins’s hand, it went off without hitting anyone. But, for even making the attempt to free himself, Beausoleil lit into Hinman and is- sued him a terrible beating. Gary still insisted he didn’t have any money to give them so they tied him to a chair and cuffed him. When he continued to resist, the whole gang took turns hammering him in the face until he eventually turned over the titles and keys to his Volkswagen and Fiat. Hinman signed them away all right, but threatened to call the police once the invaders finally left him alone. A frustrated Bobby Beausoleil telephoned Charlie back at the ranch. Manson came over with cult member Bruce Davis and brought with him a razor-sharp sword.

Manson knew if Hinman were to tell the police about all the drug and car theft dealings he had with the Straight Satans, it might lead them to investigate the shooting of Bernard Crowe, aka ‘Lotsapoppa,’ whom Manson shot and presumed he had killed only weeks before over another drug deal gone sour. Charlie had sent Tex Watson to promise suspected Black Panther associate Lotsapoppa twenty-five kilos of marijuana. They kept the $2,500 they were fronted but never delivered the pot. Crowe told them if he didn’t get his weed or his money back, he was coming up to Spahn Ranch with some pipe-wielding brothers to kill the whole Family. That’s when Charlie shot him.

Crowe survived the gunshot and never involved the police, so nobody knew—certainly not Manson, who had boasted to Family members that he’d offed a Black Panther. He hoped it would serve as a warning to others. He also worried it may have marked him for dead with the Panthers. So, in exchange for un- limited party favors with any of the girls, the Straight Satans furnished Manson with bayonets, machetes, handguns, shotguns, rifles and ammo—not a lot, but plenty enough to create havoc.

That’s where Charlie got the sword he would use to scare Gary Hinman.

Charlie threatened that if Hinman didn’t cough up all the money and shut up about the police, he was going to cut him to pieces. Hinman warned again that he would go to the cops if they didn’t leave him alone. So Charlie took his sword and struck a five-inch gash across Gary’s face that nearly sliced off his left ear. The man’s face was a bloody mess. Gary was crying and the girls were screaming and pleading with him to put an end to his own suffering. Just give them the money and be done with it.

Gary refused. Manson ordered Susan and Mary to sew up Hinman’s wounds and clean up the blood. Bobby stood watch. Charlie told him to keep putting on the heat. After Manson and Davis split from the scene (Charlie stole Hinman’s Volkswagen presumably to give to the Satans as compensation for the thou- sand bucks they’d paid for the drugs.), Atkins and Brunner stitched up Gary’s ear with a sewing needle and dental floss. Charlie left instructions for Bobby to keep up the torture and pain until Hinman succumbed.

The torment finally ended, but not abruptly, on Sunday, July 27th, after Bobby called Charlie one last time to say the torture tactic still wasn’t working.

Over the phone, Manson told Beausoleil to kill Gary Hinman, adding, “He knows too much.”

Hinman would not be the last person Charlie Manson condemned for that reason.

Hinman was stabbed five times in the chest. One or two of the wounds penetrated the sac surrounding his heart. He bled to death but not very quickly. His trio of tormentors watched for hours as he slipped into a coma, but Hinman’s lungs stubbornly continued to go on breathing, soaked as they were in his own blood. Bobby and each of the girls finally took turns smothering him with a pillow until his heart stopped beating. Once they were certain he was dead, they used his blood to write “POLITICAL PIGGY” on the wall. Bobby drew the insignia of a paw print with claws, assuming it would lead dimwitted authorities to suspect black militants were involved with the murder. Those were Manson’s instructions.

Since the Panthers’ threat he imagined had weighed heavily on Manson lately, and ever since he shot Lotsapoppa, he wanted detectives to think the Black militants had butchered Hinman over some awful drug deal gone wrong. Thus began both the real and the fake Helter Skelter. This was not a real revolution at all but rather the scam Charlie Manson used to get others to do his rancorous bidding. It was all about vengeance, paranoid delusions and money, despite what Bugliosi might have led us to think. All that shit about Helter Skelter as a race war was just a ruse.

When they hadn’t heard from him for a week, Gary’s friends went up to his house in Topanga and the first thing they noticed were the bustling torrents of insects flying in and out of the windows. Both cars were gone. Inside, they discovered the walls and floors splashed with blood and imprinted with gory inscriptions. What was left of Mr. Hinman’s corpse was shrouded in blankets of champing maggots. The whole house was thick with whirling storm clouds of red-eyed flesh flies buzzing around, like squadrons of evil jet fighters.

As ingenious and cunning as Manson and Beausoleil thought their plan was to mislead police into suspecting the Panthers may have seemed at the time, the cops didn’t buy it. Beausoleil was headed north on the run in Hinman’s Fiat when the car broke down. Highway patrolmen ran a check of the vehicle’s registration and were notified that an APB had been issued in connection with a murder. When they searched the car, police found a bloody knife in the tire well, which tests revealed had Hinman’s blood on it. They arrested and charged this criminal mastermind with cold-blooded murder.

Naturally, Charlie was worried that Bobby would cough him up to the cops. So he assured him that he had a foolproof plan for getting him off. That’s what led to the “copycat” murders at the homes of Tate and the LaBiancas, making it look like whomever killed Hinman was still out there cutting up white people’s bodies and leaving their ritual insignia on the walls in their victims’ blood.

Bobby Beausoleil was tried for the murder of Gary Hinman in November of 1969, and, remarkably, that trial ended in a hung jury. That was odd. But that just goes to show how far a pretty face can get you in Hollywood, particularly since the dunce left a bloody fingerprint at the crime scene. However, during his retrial in 1970—in return for testifying to Beausoleil’s and Atkins’s torture and killing of Hinman—Mary Brunner was granted complete immunity for her role in aiding and abetting his murder. This time the jury found Beausoleil guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced him to the death chamber. His sentence was later commuted to life in prison along with all the other Manson Family members who were later convicted in 1971.

***

NEXT: MORE ON THE HOAX ABOUT HELTER SKELTER, HINMAN, & COPYCAT MOTIVES FOR MANSON, SERIAL KILLER

Why I Wrote No Journey’s End

Why I wrote No Journey’s End: My Tragic Romance With ex-Manson Girl, Leslie Van Houten in the first person…Leslie’s actual letters to me.

Peter Chiaramonte

Why I wrote No Journey’s End: My Tragic Romance With ex-Manson Girl, Leslie Van Houten in the first person—is because that’s the only way for the reader to be certain the story is absolutely true. I had considered the epistolary POV (told through letters from various characters to one another), but chose instead to take Leslie’s letters and combine them with my own journals, diaries, newspaper clippings, photos, tape recordings, and library of philosophy, literature, history, and everything-Manson.

In my chapter 16: An Academic Prepares, you will see (when you read No Journey’s End in the next couple of weeks) how I left some of Leslie’s actual letters as letters, and with others I used the language in conversations. I didn’t want the whole book to be epistolary, as Leslie and Frank Earl Andrews once intended to do, and not do. [You may have to ZOOM-IN to 500% VIEW to see the faint pencil text of Leslie’s letter to me clearly.]

2012

When my dear friend and colleague, Albert J. Mills suggested I write a novel, I immediately began work on Moscow Prospect—a pure fiction based on my wild adventures in a few North American universities that led me to Europe, seduction, corruption in higher education, war with Russia, revolutions, and pipeline politics to boot. I began my research…then one day my daughter Mia discovered a box of letters from Leslie and, when I reread them, I changed course and started writing my story of 1976-1980 and what led me to grad school in California. How I met Leslie Van Houten took off as a memoir with a life of its own. As a writer, what’s a poor boy to do? I was hooked.

But it failed as a straight memoir. It was boring and ordinary. Too academic. Too speculate. So far remote from the action I’d actually lived through. Once again Albert Mills suggested, “Is this really the story you want to write? Why not make it into creative nonfiction? History believes the sincere and truthful novelist, not the academic historian.” I tried it again. This time something remarkable happened. Two years later, here it is: No Journey’s End.

Whose Emotions Are We Sharing; From Whose Point of View?

We live, as we dream, alone.” —Joseph Conrad

On the topic of point-of-view, here’s another smart, useful book by award-winning author and writing instructor, Nancy Kress, that I want to recommend to aspiring writers: Characters, Emotion & Viewpoint (Writers Digest, 2005). The only thoughts, plans, dreams, and feelings we can directly experience are our own, writes Kress, and I believe this is true. In No Journey’s End it’s through my eyes and gut feelings that we view all the action.

I even toyed with the notion of writing the book from Leslie’s own point of view, instead of my own. There are, after all, varying degrees of creative nonfiction. But having more journal and diary notes of my own to rely on, than even the hundreds of pages of letters and transcribed recordings from Les, I decided to stick to my own POV. Although….

I did attempt a variation of one of Kress’s writing exercises on page 171, and considered writing alternating segments from Leslie’s point of view. For example, I’d seen this technique masterfully done by Aleister Crowley in his novel from 1922, Diary of a Drug Fiend. Book I—PARADISO is told in the first person by the husband, Sir Peter Pendragon. Book II—INFERNO is told by his wife Lou. In Book III—PURGATORIO we revert once again to the first person narrative of Sir Peter.

Legend has it that—as an agreement for helping the couple overcome severe addiction to cocaine and heroin—Crowley insisted they maintain “magical diaries.” Which they did. Once Crowley possessed them, he forcibly hung on to the diaries until he’d completed his novel in 28 days, using the same drugs as he’d weaned the Pendragons of in the first place. Pretty darn cool if you ask me…

On the Crisis in Higher Education & What the Theatre Might Have to Say About it

Peter Chiaramonte

All theatre is necessarily political; because all the activities of man are political and theatre is one of them … the theatre is a weapon. A very efficient weapon … it is, in effect, a powerful system of intimidation.

– Augusto Boal, Theatre of the Oppressed

–

– Crisis, What Crisis?

Perhaps no other twenty-first century institution in society has as great a potential for shaping the lives of its constituents as does the university. Sooner or later, everyone will have a vested interest in how we advance to the highest academic degrees. Everyone has a concern with how well our society qualities new generations of professionals in every field that exists, as well as those still to be imagined. But is society getting its money’s worth in terms of the resources it takes to accomplish these aims? It appears that more than a few unemployed and under-employed university graduates are feeling stung by the prospect of having little to show for what they borrowed heavily to get (Arum & Roksa, 2011; Coté & Allahar, 2011; Fallis, 2007; Pocklington & Tupper, 2002; Slaughter & Rhoades, 2004; Woodhouse, 2009). What sequels to such plots?

Each of the above authors does a good job of reporting the news – but now is the time for going past words – and aiming to make the fundamental changes that institutional leadership for the twenty-first century will require. For example, I believe there is good reason to examine David Mamet’s Oleanna, while keeping in mind the work of Brazilian theatre artist and social activist, Augusto Boal. If we take account of the core ideas practiced in Boal’s Arena Theatre, it might help us to frame ongoing debates about gender politics and sexual harassment in a broader light and help us to act upon that stage.

In a discussion of Oleanna, if a critical approach to the play is sympathetic to the character of the student Carol, critics typically interpret the play with gender politics as their focal point (Kulmala, 2007, p. 118). If sympathetic to John, the professor, they address issues of power, language, or education as the basis of their interpretation (Bean, 2001; Murphy, 2004, p. 126; Sauer & Sauer, 2004, p. 225–26). There is no right or wrong perspective. But from an organizational–communication perspective, any of the dichotomies defaulted to out of habit can be recast, to echo the power dynamics shaping and being shaped by the institutional circumstances in which each of the players finds themselves.

Rather than exclusively attributing motive behaviour to individuals, maybe we should be taking a closer look at the dynamic social contexts in which individuals find themselves situated. Or as one reviewer put it, “to examine how the institution turns both Carol and John into vicious animals!” With this perspective in mind, we can pause the action and pose a few basic questions. For example, why do you or don’t you think the university, as an institution, might be in some sense responsible for turning both students and professors into brutal animals? And what do you think could be done to change this if it is true? Perhaps we should begin these ruminations with a synopsis of the play to look for clues in this endeavor.

Palavras Passadas (Past Words)

In 2009 at the Golden Theatre in New York, long after the final curtain fell, the producers of Oleanna took advantage of the play’s controversial power to encourage animated conversations and community action among its theatregoers. How hard would it be to try something like that on our campuses every now and again? Why not hold a few regular “talk back” forums with members of the audience, invited guests, actors (some of whom could remain in character) – and maybe have experienced Arena Theatre directors coaching the crowd and conducting the chorus. Here is some of what I can imagine us talking about: Is this play primarily about the war of the sexes, or is it something else? Is there a crisis in higher education – or is it all theatre? – just something someone has made up? Is the system working? Do these reflections of Mamet’s refract or reveal your subjective experience of university life? Was the professor sexually attracted to Carol in the first scene? Does it matter? Is Carol an abandoned young thing of some doubtful sexuality, and if so, what does this have to do with the main premises of the play? What would you guess is her secret? Is the institution somehow to blame for this sort of tragedy? Does John deserve to be denied tenure? Is he justified in knocking Carol to the floor and advancing on her with a chair raised high above his head? And so on. Does the university structure and the environment itself somehow transfigure its members into backbiting primates, or is that going too far?

At the conclusion of any drama it all comes down to the perceptions of the audience, doesn’t it? For students and professors – Oleanna is a play within a play – the meaning of which bounces of the senses within each individual’s imagination. These mirroring effects may be akin to stepping through a looking glass and – after stepping back again – finding that the image we once had of ourselves has been transformed by the experience. Let’s not guess – let’s ask them. Such is the power of the theatre and the classroom. Or, is it the theatre as classroom?

In their book, Lowering Higher Education: The Rise of Corporate Universities and the Fall of Liberal Education (2011), Western University sociologists James Coté and Anton Allahar concluded that unless some broad-based social paradigm shift occurs, university degrees will soon become little more than expensive “fishing licenses” for fished- out lakes, rivers, and streams. Still, there’s no end to the number of credentials neophytes can get with easy loans and government grants. Even if, after four years, graduates find themselves in a spot where neither the promise of wisdom nor the guarantee of a lucrative career is a foreseeable outcome.

The crisis in higher education didn’t just happen overnight. Nor will it be solved over- night. Or perhaps even in decades. The slow pace and unwieldy inertia of academic cultures, in my opinion, precludes any revolutionary turning away from the hegemonic corporate interests presently ruling the roost. Let’s be candid. For all the investment that goes into building commercial theatre space, hockey arenas, coliseums, and gambling casinos – one would think that government ministry and campus officials could discover a way to stage a little self-reflection from time to time. Surely an idea like Arena Theatre wouldn’t be too far out or bizarre for an institution that continually boasts being on the cutting edge of innovation? Let’s invite the entire university community to take part in face-to-face theatrical forums, instead of gazing at tiny screen images of each other that we fondle with our thumbs.

Personally, I love the university and the live theatre and I’d like to see them both get along and work together. I’m all for enlightened social change and not just dragging chains for the business of higher entertainment. Just as I’d like not to see the real life reflections of students and professors like Carol and John have to duke it out that way night after night – psychically and socially disabled from showing genuine respect for one another. Yes, what is portrayed as happening in Oleanna is real enough and shocking, but also inevitable. Just let’s look at the institutional circumstances!

Every time I’ve come away from a David Mamet play I’ve kept that wonderful, eerie sense that I’ve taken part in a genuine classic – a dramatic spectacle of epic stature within “my self.” With Oleanna, the playwright presents us with a tragic reflection for our times that – dare I say – one can liken to Sophocles’ Oedipus the King. Now that particular tragedy opens with Oedipus, the ruler of Thebes, lamenting the plague that has blighted his dominion. In Mamet’s Oleanna, the vicious plague infecting the academic equivalent of Thebes (New Norway U.) may just be the budget officers who run the place. Swarms of harried carpetbaggers are actively selling college loans to dreamy-eyed secondary school grads and their parents, while increasingly remote, contingent faculty study each other’s columns, graphs, and charts. Everyone looks miserable half the time, yet students are encouraged to go on smiling – expecting the entitlements of a promising future and, just maybe, some kind of intrinsically rewarding experience of lasting value. “Oh, to be in Oleanna.”

Some people will go to the theatre to see David Mamet’s play about Oleanna with similar expectations as those of us who went away to university with stars in our eyes and songs in our hearts. I’ve heard of campus productions of Oleanna where the audience left the theatre quarrelling every night with each other about all sorts of things. I have witnessed student audiences come away feeling more disturbed than disappointed. Some will be challenged to hang around after the final curtain falls and go on thinking together out loud about creating worthier institutional environments for themselves and others to take part in. Stepping through a glass darkly won’t be easy. If it were easy, then anyone could do it. But no, that’s not the academy for us. That’s not the place we came to act in, witness or applaud “As ’round the fields [we] quickly go …” [Exeunt].